The most comprehensive study on the bones of Homo floresiensis, a species of tiny human discovered on the Indonesian island of Flores in 2003, has found that they most likely evolved from an ancestor in Africa and not from Homo erectus as has been widely believed.

|

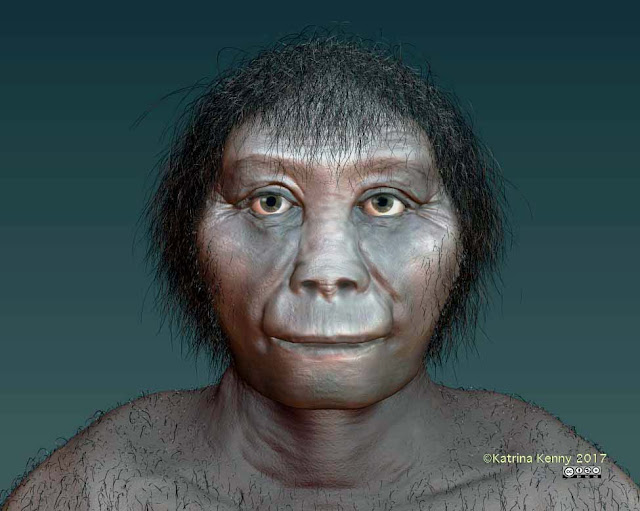

| Artist's impression of Homo floresiensis [Credit: Katrina Kenny, SA Museum] |

Data from the study concluded there was no evidence for the popular theory that Homo floresiensis evolved from the much larger Homo erectus, the only other early hominid known to have lived in the region with fossils discovered on the Indonesian mainland of Java.

Study leader Dr Debbie Argue of the ANU School of Archaeology & Anthropology, said the results should help put to rest a debate that has been hotly contested ever since Homo floresiensis was discovered.

"The analyses show that on the family tree, Homo floresiensis was likely a sister species of Homo habilis. It means these two shared a common ancestor," Dr Argue said.

"It's possible that Homo floresiensis evolved in Africa and migrated, or the common ancestor moved from Africa then evolved into Homo floresiensis somewhere."

|

| A reconstructed skull of Homo floresiensis [Credit: Stuart Hay, ANU] |

The study was the result of an Australian Research Council grant in 2010 that enabled the researchers to explore where the newly-found species fits in the human evolutionary tree.

Where previous research had focused mostly on the skull and lower jaw, this study used 133 data points ranging across the skull, jaws, teeth, arms, legs and shoulders.

Dr Argue said none of the data supported the theory that Homo floresiensis evolved from Homo erectus.

"We looked at whether Homo floresiensis could be descended from Homo erectus," she said.

"We found that if you try and link them on the family tree, you get a very unsupported result. All the tests say it doesn't fit -- it's just not a viable theory."

Dr Argue said this was supported by the fact that in many features, such as the structure of the jaw, Homo floresiensis was more primitive than Homo erectus.

"Logically, it would be hard to understand how you could have that regression -- why would the jaw of Homo erectus evolve back to the primitive condition we see in Homo floresiensis?"

Dr Argue said the analyses could also support the theory that Homo floresiensis could have branched off earlier in the timeline, more than 1.75 million years ago.

"If this was the case Homo floresiensis would have evolved before the earliest Homo habilis, which would make it very archaic indeed," she said.

Professor Mike Lee of Flinders University and the South Australian Museum, used statistical modeling to analyse the data.

"When we did the analysis there was really clear support for the relationship with Homo habilis. Homo floresiensis occupied a very primitive position on the human evolutionary tree," Professor Lee said.

"We can be 99 per cent sure it's not related to Homo erectus and nearly 100 per cent chance it isn't a malformed Homo sapiens," Professor Lee said.

Source: Australian National University [April 21, 2017]

Indonesian ‘hobbits’ not related to Homo erectus

The most comprehensive study on the bones of Homo floresiensis, a species of tiny human discovered on the Indonesian island of Flores in 200...